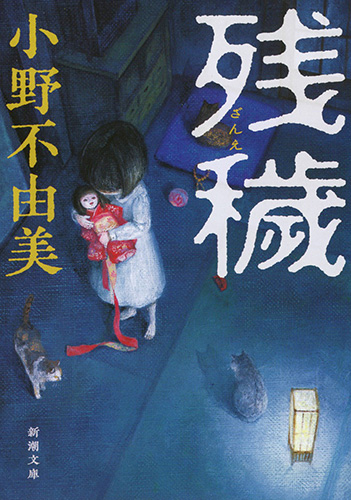

I’m not sure I’d exactly call this a review, but I read Ono Fuyumi’s Zan’e—the movie version is The Inerasable in English but I’d call it “Tainted” if anyone ever asked me—and I have thoughts.

Here’s a bit of a summary, since I’m sure not that many English speakers have read it.

The story is told in the first person by an unnamed “I” who is ostensibly Ono herself. The narrator is a Kyoto-based horror writer and collector of jitsubanashi kaidan, so-called “true ghost stories.” She puts out calls for readers of her work to send her their stories, and one day she gets a letter from a young woman named Kubo who seems to live in a haunted apartment.

Her story reminds Ono of another she’s heard before. She finds another letter in her records with the same story, essentially, sent in by another reader who lived in the same apartment building as Kubo.

And so begins a long investigation. Kubo and Ono interview other residents of the building and of the neighborhood, going back further and further in history to track the haunting. They slowly unravel a story of a diffuse, metamorphic haunting that covers the block where Kubo lives, but also seems to spread and change. They find terrible mass murders, suicides, and arson linked to it, and realize they themselves might be “infected” because the odd things follow them even when they move to new houses.

Eventually, nearly seven years after Kubo’s first letter, they track the origin of the haunting to a terrible accident at a coal mine almost a hundred years ago, on the other side of Japan.

And that’s it. The great conceit of Zan’e, and one of the reasons it has become so influential in Japanese horror is that from start to finish, it maintains the aura of real people investigating a real “strange story.” There are no great climaxes, no battles with evil, no conclusion, really. They encounter something odd, wonder where it came from, and find out.

And this book has left its fingerprints all over Japanese horror since its 2012 publication. It’s on every “Best of” or “Must Read” horror list I’ve ever seen, and authors and filmmakers alike cite it as an influence.

After reading it, I can see the influence they mean. The figure of the “kaidan collector” has become a standard trope now, with examples to be found in Kamijo Kazuki’s Shinen no Terepasu/The Bright Room, Niina Satoshi’s Sorazakana/Fish Story, and many more. The concept of “haunting as infection” is not original to Zan’e, but the evolution of that haunting from a lingering form of resentment or anger a la Sadako in Ring into essentially a mindless natural phenomenon reached its zenith here.

And then there is semi-documentary approach, without any reliance on fiction elements like plot, arc, denouement, etc. It’s just a flat record of events, some of which are really creepy or disturbing but are mostly just… Stuff happening. That has been enormously influential in the “fake documentary” style of horror that is so popular right now. Sesuji, of Kinkichiho no Are Basho ni Tsuite fame, has cited it as an influence for that reason.

For fans, it has earned a reputation as one of the most frightening horror books in the Japanese language. And I get it! At its core, what Zan’e presents is a cosmology that truly is terrifying.

The basic idea is based in the Japanese spiritual concept of kegare. Kegare is a taint, a metaphysical stain that gets on people who come into contact with things considered unclean: death, blood, rot, filth, and (in the dreadfully misogynistic ways of olden days) things involved with being a woman like menstruation and childbirth.

Zan’e takes up kegare based on the very traditional idea that a place where people die is stained by that death. Usually that stain fades naturally, but in her book Ono speculates that perhaps, if more death happens there before it fades, the stain is intensified, and so a cycle can begin. Couple that with the idea that people who simply go that tainted place—simply be present—then become carriers of the kegare, and you begin to see the danger.

Then, she postulates that the very intense kegare may carry echoes of the death, or the deceased’s state of mind at the time. Their misery, or anger, or pain. The stain whispers, it weeps, the sound of a suicide’s belt dragging over the floor lives on in the stain. What if some people are more susceptible to the influence of the kegare than others? The sounds and visions of shadowy figures truly disturb them, the voices whispering in their ears successfully convince them to kill others and themselves… Won’t that create a new, stronger stain? And on and on, ad infinitum…

This is the terrifying heart of Zan’e that made one award judge say “I don’t even want to put this book on my shelf.”

But. With all that said, I don’t know that I would recommend this book to anyone except horror completist nerds (like me). Because this book is dull. Deadly, painfully dull. Which could well be the intention, given the dedication to the realistic style. Anyone who has ever interviewed members of the public knows that most people just aren’t good at telling stories. They meander, they repeat themselves, they get confused. And given that much of this book is a documentary-style record of just such interviews, you get all of that.

There is, for example, a twenty page chapter that is just one elderly neighbor of Kubo’s talking about all the many people who have moved in and moved out, the buildings that have gone up and come down, the changes over the years… You know, old people stuff. Within that twenty pages are roughly two paragraphs that actually pertain to events of interest. The rest is simply there to add weight to the idea that some houses in this neighborhood just don’t get lived in long. Which isn’t all that interesting a point.

I would say that basically nothing interesting as such happens for over half of the book. It’s all just talking, with hints of the taint scattered through to keep the monologues relevant to the story. So. Dull.

I had to force myself to finish Zan’e. I only did it because I want to better understand modern Japanese horror, and it’s such an influential book that I felt it necessary. But God, it took me forever.

The movie is pretty good, though.