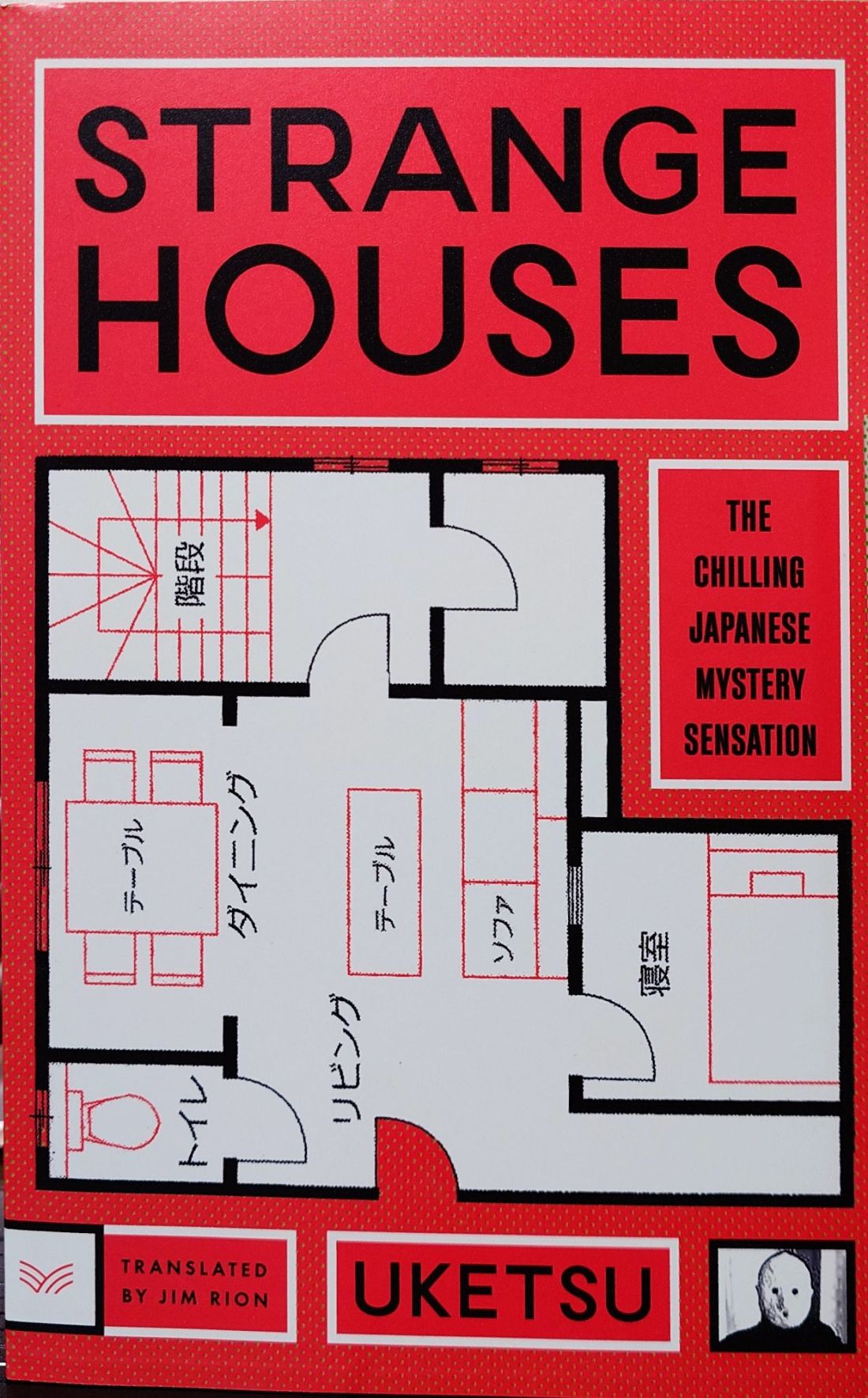

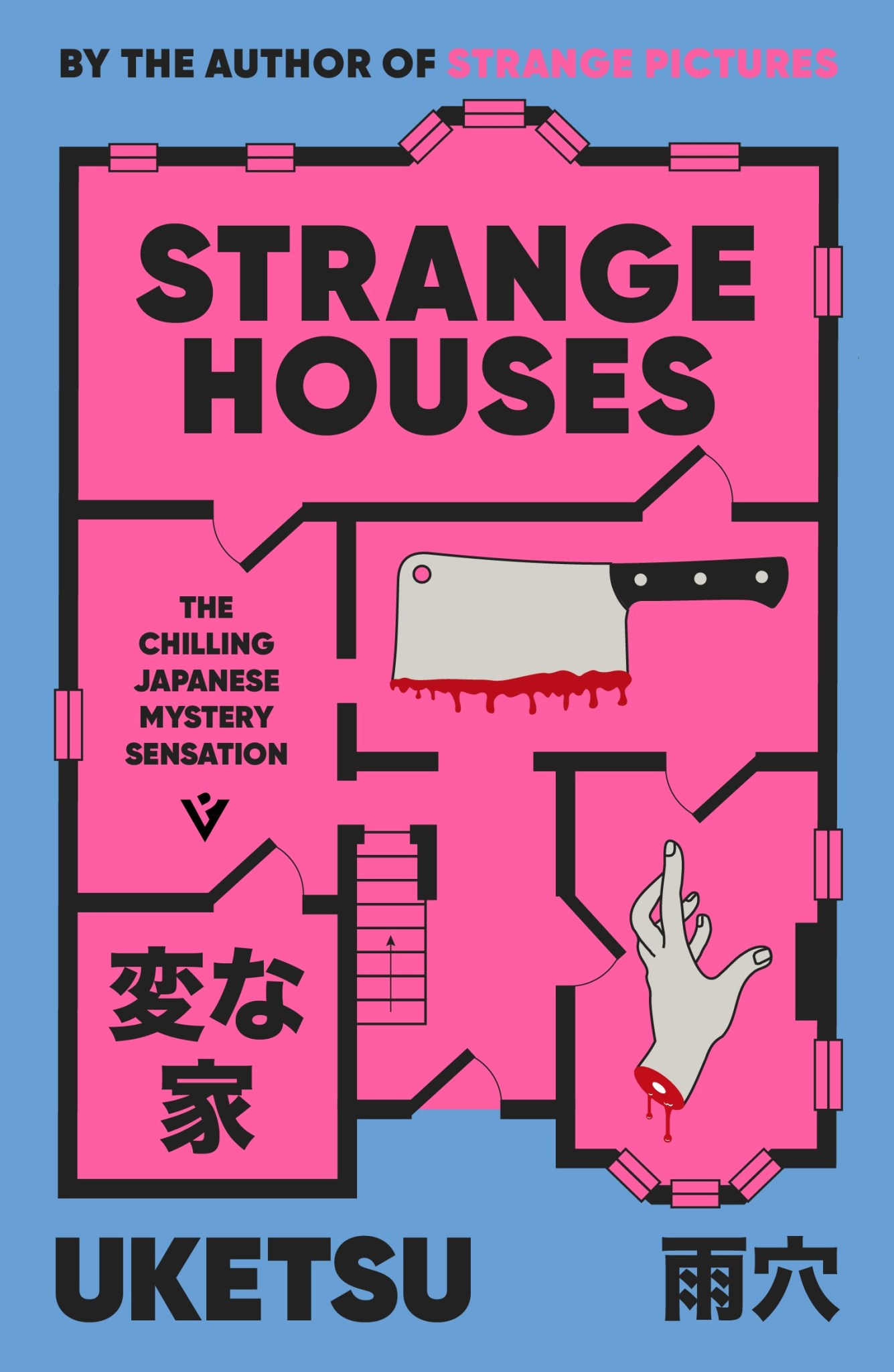

It has been a couple of months since Strange Houses, Uketsu’s debut novel in Japan and second in English translation, came out in both the US and UK. I figure it’s about time to address some of the particular issues translating this one, given that people have probably had a chance to read it.

Just to warn you, this is not a spoiler free effort. I won’t go out of the way to include hidden details, but I’m going to go where I’m led.

So.

To recap a bit, I first encountered Uketsu as a YouTuber. My wife became a fan during the height of the pandemic and introduced me in 2022. I shared her interest, but being more interested in books than videos, I was pleased to see that he was also publishing books. Strange Houses actually began from a long-form video and a simultaneous story published on the fiction site Omokoro. An editor at the publisher Asuka Shinsha then reached out to Uketsu and said it would make a great novel if expanded. The existing story became the first chapter of the novel, and I think this helps explains some of the roughness that people might notice in Strange Houses as a whole. Don’t get me wrong, I love the mood and characters it introduces, but in terms of storytelling it is a little loose. And the ending is… Eh. It has its flaws, though I honestly believe the charms outweigh them.

That story is about a friend reaching out to Uketsu about an odd house he was thinking of buying. Poking into the house’s design, Uketsu’s other friend, Kurihara, speculated that the house had been designed for the purpose of murdering and dismembering people. The original friend ended up not buying the house because a dismembered body was discovered in a nearby wooded area and it just felt like a bad omen.

Now, here is where we get to the “translation issue.” In the original publication, that first dead body—the dismembered body missing its left hand, which becomes a significant plot point as other bodies missing hands are discovered—is never mentioned again. The conclusion seems to wrap up all kinds of plot points, but no one even says “Hey, what about that one guy.”

The English editor and I were both rather nonplussed by that. It seemed a rather significant plot point, indeed the instigating incident for the whole book, to just let fade into nothing.

We reached out to Uketsu about this, and about the possibility of adding something, even some simple comment like “It’s crazy that the first body was just a coincidence” so it didn’t feel like people just forgot about a whole dismembered body.

His response was initial surprise, since, as he said. “In the two years since publication not a single person has even asked about that.” But then he said that there was a new mass market paperback edition (or bunkoban) coming out in Japan with a new Afterword “by Kurihara,” which added some doubts and twists to the story as recounted by the fictional Uketsu. Real world Uketsu proposed both adding the Afterword to the English version and making some adjustments that would incorporate the initial body into the doubts Kurihara expressed, which was both a rather neat solution to our doubts and a very cool idea in general.

What this also means is that the English version of Strange Houses is in a very real way a different story from either version in Japanese—and I want to emphasize, it was made so by Uketsu himself. This wasn’t some rogue decision by the editor and I.

I think this should tell you something about the “literary” translation process. On top of cultural/linguistic issues, translators are some of the closest readers you’ll ever find. We dig deep, deep, deep into the stories we translate because, honestly, most of us are terrified of missing something important. We get confused. Sometimes it’s because we do miss things. Sometimes it’s because the author missed something. And sometimes it’s because of a gap in values, world-view, or cultural assumptions. And that’s where we, as translators, start to dig and clarify so we can ensure that the readers of the translated story have the best experience possible.

It also speaks to the role of editors. I think many people assume that in publishing, the author is some kind of towering, monolithic talent whose words are inviolate. It just isn’t true. Editors have enormous power to shape a story and even an author’s voice, and almost always for the better. You think it’s a coincidence that F. Scott Fitzgerald, Thomas Wolfe, and Ernest Hemingway all just happened to be discovered by the same editor? Look up Maxwell Perkins. It is an edifying example of how editors can influence literary output. The same is true of translation, perhaps even more so. See my review of Who We’re Reading when we Read Haruki Murakami for more on that.

So, yeah, it turns out that published stories are far more collaborative than is often believed. That’s not a bad thing! It makes the experience better for readers, if a bit stressful for writers…